“Consumer electronics are driven by silicon but follow the natural laws of the carbon-based world: survival of the fittest.

The mouse is over 60 years old, yet its design has barely changed. Computers have evolved over the past 70 years, shrinking from room-sized machines to everyday appliances and personal devices. In contrast, products like pagers, GPS units, and iPods became mere memories before they had a chance to truly evolve.

We continuously examine evolving products of tomorrow: What ideas birthed them? How do they persist through change? How do they shape new lifestyles, and how are they transformed by users?

Let’s check out DJI’s new drone first. It has an abstract design that reminds me of a foldable bicycle.

Even among DJI’s extensive drone lineup, the DJI Flip stands out as the most unique.

At its launch, DJI spokesperson Daisy Kong clearly defined its purpose: “Like the DJI Neo and DJI Mini, the DJI Flip is developed to cater to different types of beginners.”

Bringing Aerial Photography Within Reach

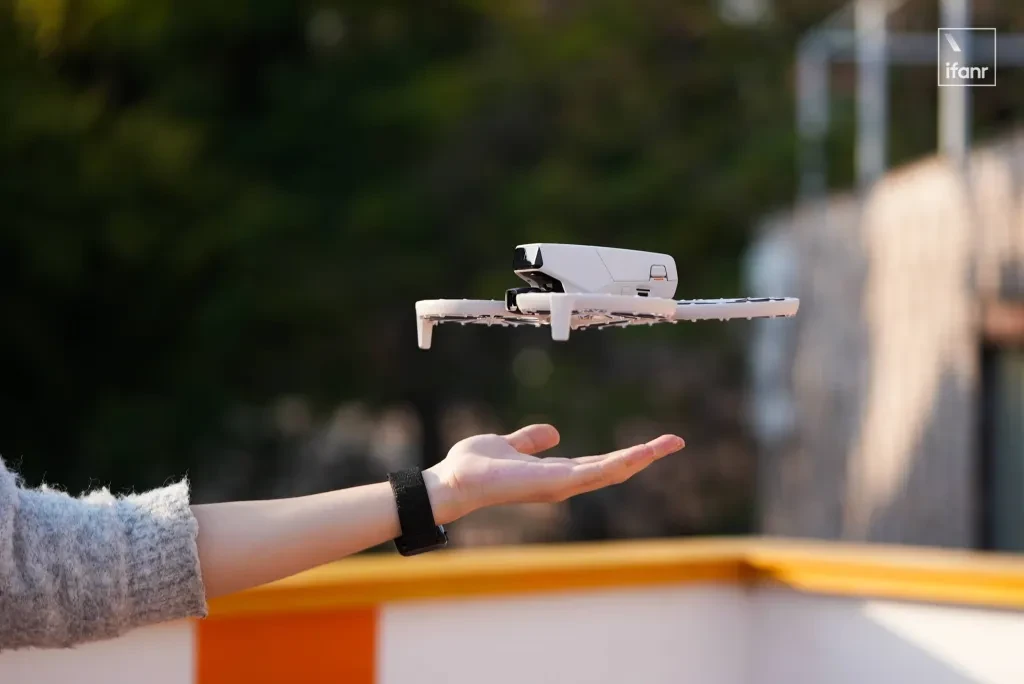

In DJI’s vision, a drone experience that instantly dispels beginners’ concerns is one that takes off from the palm of your hand.

This straightforward operation showcases the drone’s safety and ease of use, bridging the gap between the device and the user.

To ensure beginners can fly with confidence, the Flip draws inspiration from DJI’s FPV series, featuring a propeller guard and a design approach first seen on the DJI Neo a few months ago—providing comprehensive protection for the top and bottom of the propellers.

To meet lightweight requirements, the Flip optimizes the material of the upper and lower enclosures, using over 30 carbon fiber rods to enclose the space above and below the propellers.

Carbon fiber is renowned for its exceptional performance, offering the same stiffness at just 1/60th the weight of traditional engineering plastics like PC, reducing overall weight while providing robust support for the outer protective guard.

To minimize crash risks, DJI has, for the first time, equipped this small aerial photography drone with front obstacle avoidance, featuring a three-dimensional infrared sensing system above the camera that effectively detects obstacles in front, regardless of lighting conditions.

The large size of drones often deters many users, so in addition to eliminating crash risks, the Flip’s compact and portable design is another selling point.

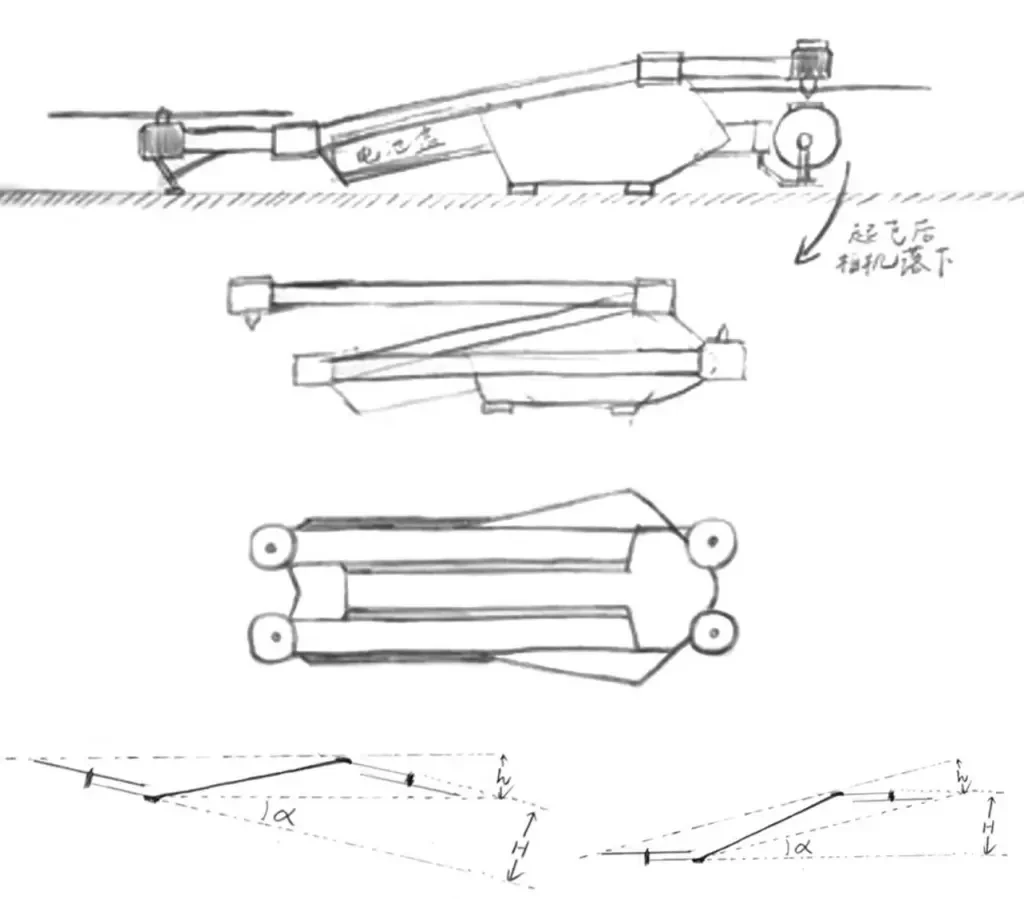

Building on the success of its predecessors, the DJI Flip inherits the excellent folding design of the Mavic series. However, due to the presence of the propeller guard, unlike the Mavic series, which folds the arms to the sides, the DJI Flip opts to fold the rotors downward.

Once folded, the DJI Flip’s four arms stack neatly at the bottom, resembling a unicycle from the side. The real marvel is its folded thickness—just 62 mm, comparable to a fast-charging phone adapter, making it easy to fit into any backpack or even a large pocket of a jacket.

Besides portability, the folding action also serves as the power-on mechanism. When all four arms of the DJI Flip are fully extended, the power automatically activates, eliminating the previous “short press then long press” complexity.

With powerful visual algorithms, the DJI Flip easily identifies subjects, automatically adjusts flight paths to keep the subject centered, and offers various intelligent shooting functions, making it almost intuitive to operate.

Additionally, the DJI Flip introduces voice commands for the first time. Although the commands are fixed, they are sufficient to bring the complex skill of aerial photography within a step of the user.

The deep integration of hardware and software, combined with a 30-minute flight time and a 249-gram body weight, makes the DJI Flip possibly DJI’s most user-friendly entry-level drone to date.

Simplifying complex tasks is a golden rule repeatedly proven in the history of human commerce.

And looking at DJI’s development history, it’s a story of evolving aerial photography from difficult to simple.

Ready-to-Use, Grab-and-Go

In 2006, Frank Wang founded DJI Innovations in Shenzhen, China, but it wasn’t until 2013 that their first aerial photography drone, the Phantom, hit the market.

The Phantom, equipped with a GPS positioning system, supported simple aerial photography. It wasn’t exactly smart, requiring operators to undergo extensive training to confidently capture decent footage without crashing—yet it was a breakthrough step for consumer-grade aerial photography.

At that time, aerial photography drones were still in a niche market, mainly used for geological exploration, industrial surveying, and film production—high-end fields with expensive equipment, complex operations, and high technical barriers, making it impossible for ordinary enthusiasts to bear such costs, forcing them to seek alternatives.

Thus, DIY aerial photography drones took the stage.

Technically inclined enthusiasts gathered to research various DIY solutions and shared them openly on forums like RC Groups and DIY Drones.

These DIY solutions were mainly divided into three categories: remote-controlled helicopters, multi-rotor drones, and fixed-wing drones.

The remote-controlled helicopter and fixed-wing model drone solutions followed the flight principles of traditional mature aircraft, achieving miniaturization and civilian use through multiple iterations while retaining the lift structure.

However, due to their flight forms, these solutions, though refined, still couldn’t achieve perfection: the remote-controlled helicopter solution was mature enough to carry lightweight cameras for shooting but was difficult to operate and prone to crashes, while the fixed-wing aircraft solution, inherited from military use, could perform long-distance aerial photography but couldn’t hover for shooting.

The rise of multi-rotor drone technology around the millennium can be attributed to the development of forums like RC Groups and DIY Drones. This new form is more stable than remote-controlled helicopters, with multiple propellers offering comparable maneuverability and the ability to hover for extended periods, making it the best choice for civilian use.

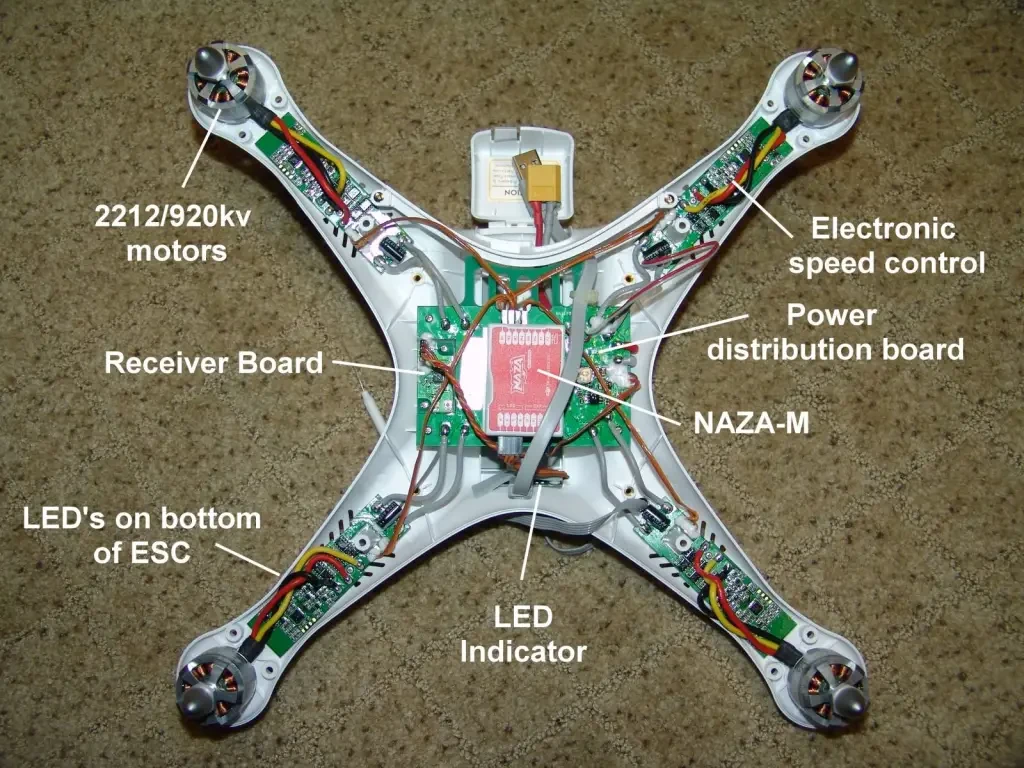

At this time, DJI, holding the core of drone technology—the consumer-grade flight control system NAZA—keenly observed the market’s lack of a “ready-to-fly” aerial photography drone while collaborating with global developers and professional users.

Ensuring cost-effectiveness while launching its own hardware became a natural progression.

Thus, the world’s first consumer-grade aerial photography drone, the Phantom, was born.

Interestingly, when the DJI Phantom was initially released, it did not include a gimbal or camera. Users could mount action cameras like GoPro using the fixed bracket below the body. It wasn’t until later that the Zenmuse H3-2D gimbal, designed specifically for the GoPro Hero, was introduced, highlighting the Phantom’s primary goal of integrating multi-rotor drone solutions.

Looking back, the launch of the DJI Phantom 1 directly eliminated the DIY technical barriers faced by enthusiasts, bringing aerial photography drones into the consumer market and ushering in the “ready-to-fly” era.

In 2016, DJI released the Phantom 4.

While its exterior still followed the multi-rotor drone design with little change, its internal structure underwent a complete transformation. The Phantom 4’s circuit board was more integrated, with nearly all functional modules concentrated on a single mainboard, integrating power distribution, flight control systems, and sensor interfaces, reducing unnecessary wiring.

The more intelligent flight control and obstacle avoidance systems also gave the Phantom a complete overhaul in terms of its “brain.”

However, at that time, DJI founder Frank Wang believed drones were still not user-friendly enough:

“We believe the drone market will continue to improve and has room for growth. One of our plans for the next three years is to make our products more user-friendly.”

It’s important to note that the “room for growth” Wang mentioned was not about DJI but the drone market itself. In other words, from this point on, DJI decided to expand the drone market.

This is a logical progression: to expand the market, you need to attract more users, and to attract more users, you need better products.

To make drones more user-friendly, they first needed to be portable.

Thus, on September 27, 2016, DJI launched a groundbreaking drone—the Mavic Pro.

The Mavic Pro continued the performance level of the Phantom series, but its most distinctive feature was its foldability.

In later reflections, Mavic Pro’s designer and current LEAPX design studio founder, Rainy Deng, commented: “This isn’t the world’s first foldable drone, just the best one.”

During the Phantom era, although DJI eliminated the complexity and instability of DIY, making drones ready to fly out of the box, the Phantom’s large size required storage in a massive foam box, which was the biggest barrier to using the Phantom series drones.

After all, the photography rule “step out of the house to take good photos” also applies to aerial photography.

The Mavic series adhered to the main structure of the multi-rotor drone design, choosing four propellers like the Phantom series, but unlike the Phantom, the Mavic series’ arms could fold.

Thanks to the integration experience from the Phantom series, DJI further optimized the core design in the Mavic Pro, significantly reducing component size.

From the internal structure diagram, its mainboard is located at the center of the body, serving as the control core, integrating flight control, power distribution modules, and other electronic units, significantly simplifying the wiring structure. Meanwhile, visual sensors connect to the mainboard via dedicated interfaces, supporting obstacle avoidance and positioning functions. The ESC module is directly integrated into the mainboard to drive the brushless motors, making it more compact than traditional distributed designs, reducing the risk of component dispersion-induced failures, and enhancing overall reliability.

After highly integrating the core components, DJI removed the redundant casing from the Phantom and set pivots at the four corners of the rectangular body, allowing the propeller arms to fold alongside the body when not in use.

The positive impact of this design change is evident—when folded, the Mavic Pro’s size is almost one-twelfth of the Phantom 4, solving the Phantom series’ large, non-portable issue, making aerial photography drones truly portable, ready to fly out of the bag.

If we evaluate technological advancement in a simple, direct manner, there’s a saying:

“Humans are obsessed with making things smaller because, in the history of technology, smaller often means higher integration, lower power consumption, and thus more advanced technology.”

From this perspective, the Mavic Pro, released six months later, is a groundbreaking product. Although it didn’t achieve a qualitative leap in performance, its new portable form factor revolutionized DJI’s own Phantom series, ushering in a new era.

Since then, aerial photography drones have rapidly gained popularity. As a photographer, the most noticeable change is that friends interested in aerial views have gradually purchased a DJI drone, and aerial photography works have increasingly appeared on social media.

However, evaluating products based solely on “anecdotal evidence” is certainly biased, but data doesn’t lie.

According to a report by the Qianzhan Industry Research Institute, the Chinese civilian drone market reached 59.9 billion RMB (approximately $8.2 billion) in 2020, three times the size of 2016. In this growing drone market, thanks to the Mavic series, DJI quickly extinguished the anxiety of 2016. Just four years later, DJI held over 70% of the Chinese market share and 80% of the global market share, becoming the undisputed leader in the aerial photography drone market.

Three Challenges Pointing to the Future

In the article “The Design Story of DJI Mavic” written by Deng Yumian after completing the Mavic Pro, he uses a Q&A format to outline a vision for products that surpass the Mavic.

Interestingly, as consumers, we often focus more on the video specifications of aerial drones, but for designers, the three challenges presented have nothing to do with video specifications:

- Drones still have noise and propeller injury risks.

- The usage scenarios for drones are limited; we need to find ways to encourage more people to try them.

- Drones are not intelligent enough.

“If any of these three problems are well solved, Mavic might be surpassed. I wonder if the next product to surpass Mavic will be Mavic itself? I look forward to the arrival of the next breakthrough product.”

Just as Mavic revolutionized the Phantom series, DJI still wants to take control of tomorrow’s products. Thus, DJI began to address some of these issues.

In 2019, DJI was making waves, launching the RoboMaster S1 educational robot and the Osmo Action sports camera, rapidly expanding its business footprint. That year coincided with the timeline mentioned in Wang Tao’s interview, “making products easier to use in about three years.”

As the foundation of its success, the Mavic series was quiet at that time, but another important series emerged from the Mavic line—the DJI Mavic Mini.

This drone weighs only 249 grams, eliminating the need for registration in many countries and regions. Compared to the Mavic 2 series drones of the same period, the Mini reduced its body size but still offered a flight time of up to 30 minutes, creating a sensation.

Along with the first-generation Mini, the accompanying app—DJI Fly—was launched.

Compared to the DJI GO 4 used by the Mavic series, DJI Fly integrates a one-tap short video mode. Users can easily operate within the app to control the DJI Mini to automatically perform maneuvers like droning, circling, and spiraling. It also offers quick video editing and sharing features, eliminating the need for complex editing to process and share videos on social media.

The appearance of the DJI Mavic Mini addressed some of the challenges posed by Deng Yumian: Limited usage scenarios for drones—Mavic Mini reduced body size and weight, lowering the barrier for users to take it outdoors, while avoiding registration management in most regions;

Drones are not intelligent enough—With the launch of DJI Fly alongside Mavic, it not only functions as a remote control but also incorporates many intelligent operations, making it smarter.

Although specific sales data has not been disclosed, the rapid evolution of the Mavic Mini into an independent product line after its first generation undoubtedly proves the success of the Mini series.

However, it is worth noting that the Mini, which solved some problems, did not replace the Mavic series like Mavic replaced the Phantom series. Instead, through clever video specification limitations, it formed a “high, medium, low” tiered lineup with the Mavic series and Air series, covering the market for aerial photography and photography enthusiasts.

This is also DJI’s method of expanding the “drone pie.”

Let’s review DJI’s product iterations.

In the first era, the Phantom series targeted professional groups, focusing on stability, eliminating the uncertainties of the DIY phase, and providing an industrialized, reliable professional drone. In the second era, the Mavic series aimed at a broader enthusiast group, breaking through with portability and high performance, allowing ordinary consumers to easily enjoy aerial photography.

After the initial success of the Mini series, DJI continued to pursue more accessible products with the same approach.

Thus, we saw the DJI Neo with fully enclosed propellers for safer drones, and the DJI Flip with stronger performance, more foldability, and greater intelligence.

Including the Mini, this is already DJI’s third model in the entry-level category with subtle differences.

At this point, I think things are becoming clearer.

Different environments, different user needs, and different products at each stage, but DJI’s approach has always been consistent—using design and technology to make drones more user-friendly and popularize them among more people and broader groups.

The Sky Can Be Everyone’s Utopia

In 1997, Chongqing became a municipality of the People’s Republic of China, and Chongqing TV planned a large aerial documentary “Bird’s Eye View of New Chongqing.”

At that time, the aerial photography solution involved holding a camera while shooting from a manned helicopter.

High-altitude panoramic shots were relatively easy, but completing shots like flying through the Yangtze River and Qutang Gorge required the helicopter to skim low over the river between towering mountains on both sides.

This not only demanded high piloting skills from the helicopter pilot but also tested the photographer’s shooting abilities.

In 2015, shortly after the start of filming for the seventh edition of “Bird’s Eye View of New Chongqing,” a helicopter carrying two pilots and two crew members crashed in Liangping County, resulting in the loss of all onboard personnel, who sacrificed their young lives for the cause of imagery.

Since humans mastered photography, aerial views have been like a window, bringing new understanding and narrative methods to the world. To pursue this unique perspective, humans have tried every means and paid the price.

Starting in the 19th century, photographers had to climb into hot air balloons with bulky film cameras, braving wind speed and gravity challenges, struggling to overcome balance and stability issues to conduct aerial photography. Later, cameras were mounted on propeller planes, and photographers boarded to shoot, pioneering modern aerial photography. By the latter half of the 20th century to the early 21st century, helicopters became the most mainstream aerial photography tool.

Behind the evolution of aerial photography technology were high time and material costs, as well as unavoidable safety risks, making aerial photography almost irrelevant to ordinary people for over a century.

Until a young company emerged, using twelve years and a series of products to steadily and swiftly change the high cost, high risk, and low popularity of aerial photography, granting more people the right to “fly into the sky.”

“From the beginning, we had a vision that DJI would become a utopia.” — This is the vision conveyed in DJI’s 16th-anniversary brand promotional video “Utopia.”

Although utopia remains elusive, the sky, once belonging only to a few, is becoming everyone’s domain.

Source from ifanr

Disclaimer: The information set forth above is provided by ifanr.com, independently of Alibaba.com. Alibaba.com makes no representation and warranties as to the quality and reliability of the seller and products. Alibaba.com expressly disclaims any liability for breaches pertaining to the copyright of content.